In a world where resources are finite, circular thinking is transforming discarded materials into profitable opportunities. Turning Waste into Value with Circular Supply Chain Finance illustrates how businesses can harness traceability and innovative financing to unfold hidden value from materials that would otherwise go to waste. By tracking every stage of a product’s lifecycle, companies gain the transparency needed to optimise reuse, recycling, and refurbishment. At the same time, financing mechanisms provide the capital required to scale these circular solutions, turning sustainability from a moral imperative into a measurable business advantage.

The most forward-looking companies have realised that circular supply chains cannot function on recycling slogans alone; they require infrastructure, data integrity, and most critically, finance.

At the centre of this transformation lie two interconnected forces: traceability; the ability to prove a product’s material story, and financing, the ability to unlock capital based on that proven future value. Traceability makes resources visible; finance makes them viable. One without the other leads to stalled ambition. Together, they lay the foundations of a new industrial system, where value is not extracted and discarded, but retained, redeployed, and reinvested.

Traditional supply chains are linear by design: materials move from extraction to production, into consumption, and finally to disposal. Value is captured at the point of sale, and everything beyond that; returns, repairs, materials, is treated as cost.

Circular supply chains invert that logic. They recognise that value does not end at the first sale. Products hold residual value — in components, raw materials, refurbishment potential — but only if they can be identified, verified, and reclaimed. And that is where traceability acts as the crucial bridge.

Traceability is often misunderstood as a compliance tool. In a circular system, it becomes a currency. It records origin, composition, ownership, maintenance, and end-of-life pathways. It answers the questions a recycler, insurer, or financier would ask: What is this item? What is it made of? What condition is it in? Can we verify its history?

Currently, regulators are accelerating this shift:

But beyond compliance, traceability creates clarity. That clarity reduces risk — and where risk disappears, finance follows.

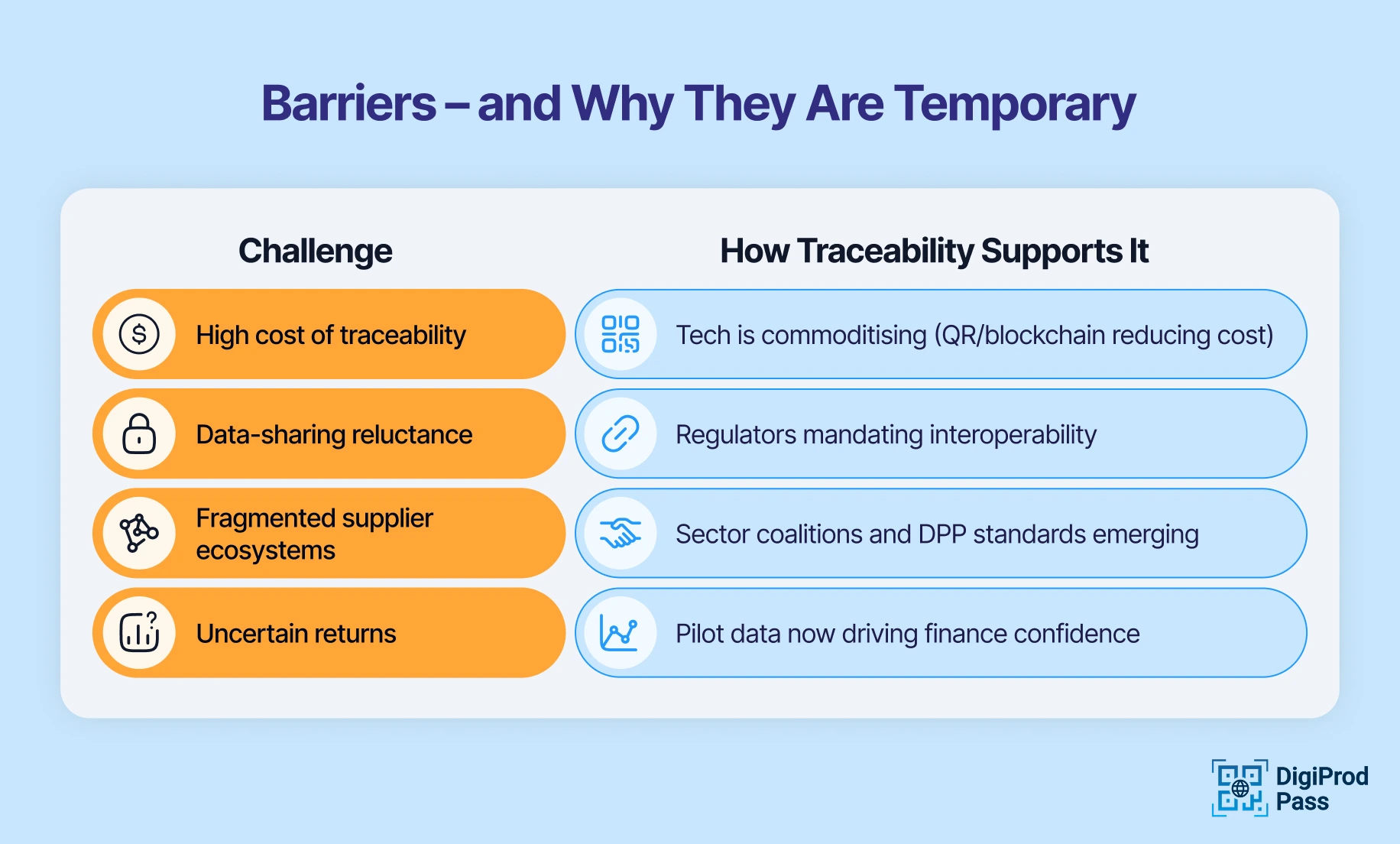

Moving to circular operations demands investment. New reverse logistics networks, repair facilities, refurbishment centres, material sorting technologies — all require upfront capital. Yet traditional finance struggles to fund these models, largely because circular returns are deferred and uncertain.

Here is where traceability becomes transformative: it allows financiers to see the future value stream.

In essence, traceability converts circular ambition into bankable assets.

The Digital Product Passport is not just a technical upgrade; it's a structural redefinition of product identity. A DPP assigns each physical product a persistent digital twin, holding:

For a financier, this is gold. It allows them to forecast recovery rates, resale potential, and resource yield, enabling them to underwrite circular activity with confidence.

In the past, second-life assets were unverifiable. With passports, they become investable.

Financial institutions operate on certainty. To fund a project, they need proof of value and proof of return. Linear manufacturing provides that proof via purchase orders and inventories. Circular systems must replace this with lifecycle visibility.

Here are three ways traceability enables capital deployment:

This marks the birth of what some are calling the “inverse supply chain”, where end-of-life becomes the beginning of new capital flows.

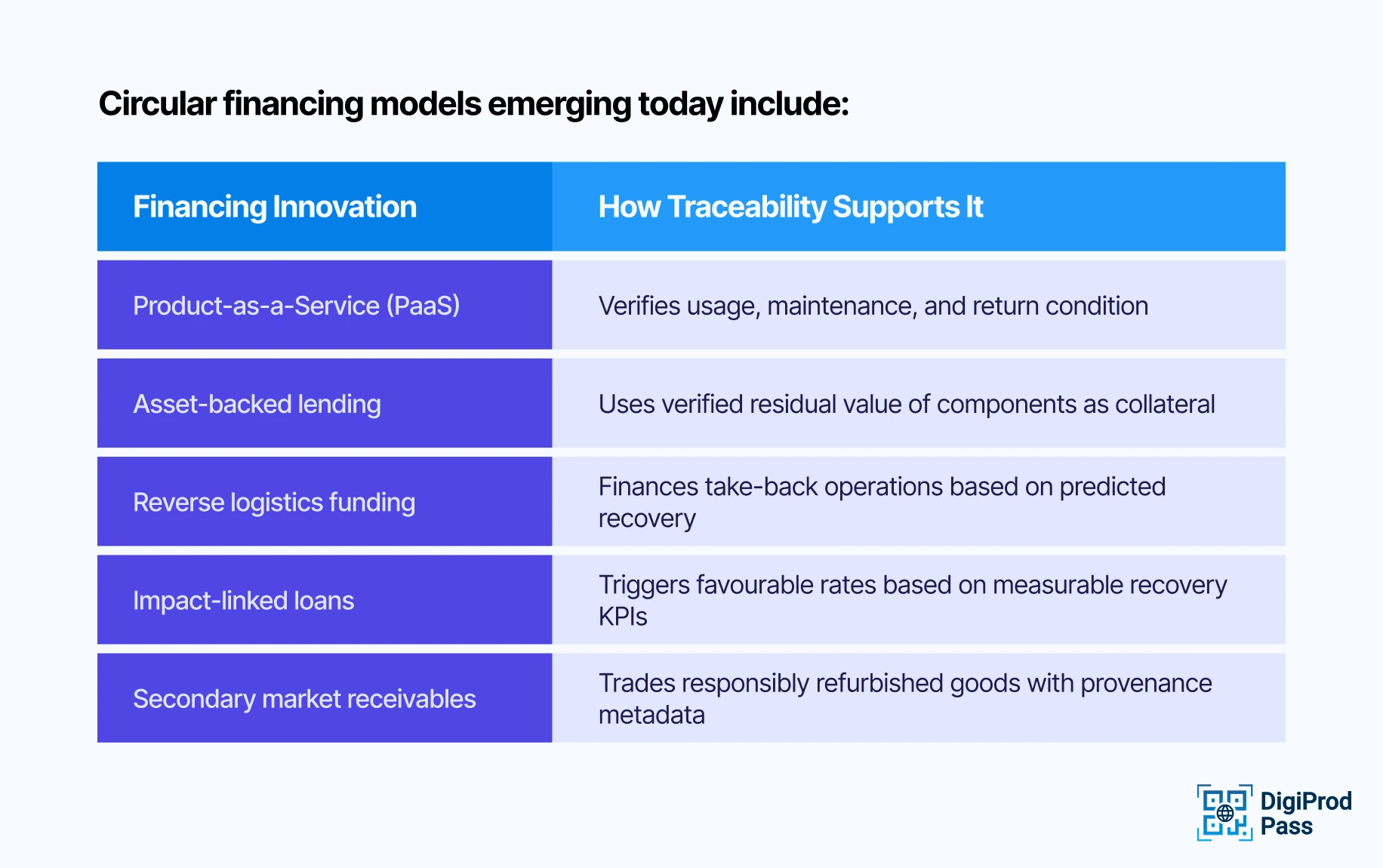

Real advantage arises when companies fuse traceability with business innovation. Some of the most advanced models include:

Manufacturers retain product ownership and lease usage. Traceability enables maintenance schedules and return tracking, which increases lifecycle value.

Used in electronics and fashion. Customers pay a deposit, returned when the product is sent back. Traceability ensures correct identification and quality assessment.

Platforms for certified recycled materials rely on verifiable origin. Traceability ensures premium pricing and trust in quality.

Large buyers, such as automotive or construction firms, contract recycled material suppliers, but only if the provenance is proven.

Policymakers are no longer observers — they are now enablers. The EU has laid down a blueprint that other jurisdictions are expected to follow:

Regulation is shifting from “polluter pays” to “producer proves”.

The companies that act early will not only avoid penalties, but they will monetise leadership.

Success in circular supply chains is not measured in tonnes recycled alone. It must quantify financial and material continuity:

Key Metrics to Track:

Boards and investors increasingly request precisely these metrics, especially under CSRD reporting and ESG-linked finance.

Businesses being able to adopt traceability earlier gain a decisive edge with first access to green capital, customer trust, and most importantly, regulatory goodwill.

The transition to circularity is not a recycling challenge; it is a data ownership challenge. Those who control lifecycle data will control:

Traceability is no longer a supply chain function. It is a board-level asset.

In the near future, board discussions will include a new term: invisible inventory, untapped material value circulating outside ledgers and balance sheets. The circular economy is the process of making that inventory visible, measurable, and tradable.

Traceability provides the evidence, financing provides the engine; together, they are not an environmental initiative, but a financial revolution.

The question is no longer “Should we go circular?”

It is “Do we control our value, or does it leak unseen into waste?”

https://environment.ec.europa.eu/strategy/circular-economy_en

https://environment.ec.europa.eu/topics/circular-economy/first-circular-economy-action-plan_en

.svg)

.svg)